Build it and they will come

What we’ve learned from building naming architectures

At A Hundred Monkeys we have a singular focus for most of our naming projects. We’re naming one company or one product. A smaller subset of our work is focused on naming multiple products that make up a brand’s portfolio. We call this work naming architecture. My colleague Nora wrote a piece on how we think about the work, which serves as a great primer on the subject.

We love these projects because they’re more complex than a straightforward naming engagement. Creating a naming architecture allows us to more fully engage the two sides of our brains: we must be rational and think systemically while we look for opportunities to be creative and playful.

The goal of a well constructed architecture is to help consumers understand which product is right for them. If you’ve bought a smartphone or a car or, really any product from a company that sells multiple products, you’ve successfully navigated a naming architecture.

If your selection process was smooth that naming architecture was well thought out — despite the fact that you may not have thought about it that way. If your selection process was less than smooth, that naming architecture was likely poorly constructed.

We’ve been creating naming architectures for a long time. The most complex of which is still in process, as we’ve been helping a major international brand sort out their ever evolving product line up for the past four years.

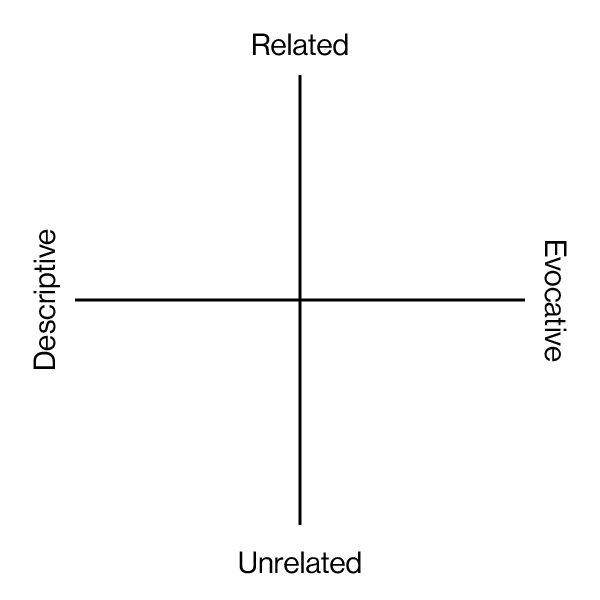

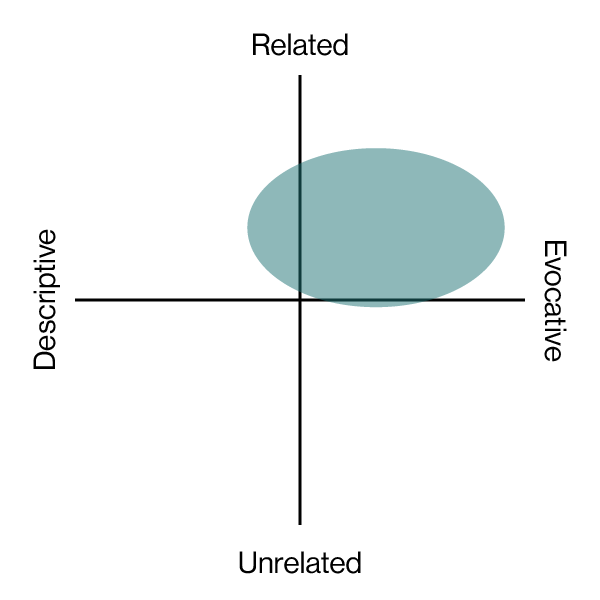

One element we’ve developed is how to map a given architecture. Our map looks like this:

To better illustrate our method, I’ll map out a few well known product portfolios.

However, before we look at some architectures let’s define the terms we are using here.

Architecture: A system for applying product names across a product portfolio to help customers understand which product is right for them.

Evocative: Evocative names use metaphoric, illustrative, or imaginative language to capture what it is the name is naming, e.g., Burton Snowboard’s Deep Thinker Snowboard is built for floating in powder.

Descriptive: Descriptive names use straightforward language to characterize the purpose of a product, e.g., the Rolex Day-Date displays — you guessed it — the day and the date.

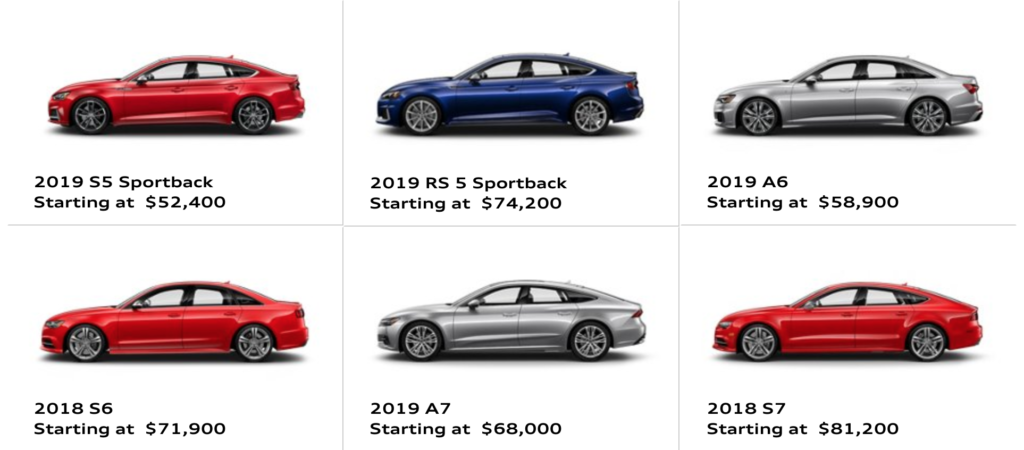

Related Architecture: An architecture where the names are highly coordinated. An prime example is Audi with their A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8 names for standard models; S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8 names for sport tuned models; RS4, RS6, RS7 for “Renn-Sport” or racing sport models; and R8 and R8 Spyder for their supercars or, more or less, racing tuned models.

Unrelated Architecture: I’ve yet to find a system that is wholly unrelated, however relative to tight systems like Audi’s, plenty of brands employ a looser naming architecture across their products. Rolex is a decent example: Rolex classic watches are a mix of descriptive (Day-Date, Datejust, Lady-Datejust) and evocative (Cellini, Pearlmaster, Sky-Dweller). Their professional range naming is more evocative: Explorer, Submariner, Sea-Dweller, Air-King.

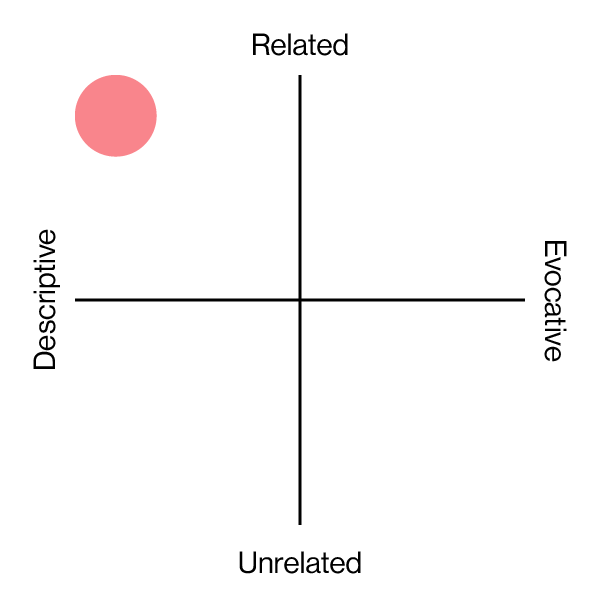

Here’s how Rolex maps out:

A portfolio with both descriptive and evocative names.

Classic watches: Datejust, Day-Date, Cellini, Lady-Datejust, Pearlmaster, Oyster Perpetual, Sky-Dweller.

Professional watches: Yacht-Master, Cosmograph Daytona, Submariner, Sea-Dweller, Explorer, GMT-Master II, Air-King, Milgauss.

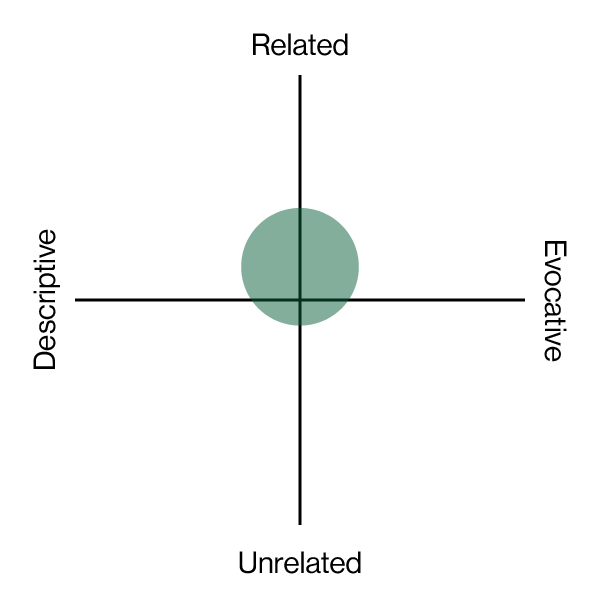

Here’s how Audi maps out:

A very descriptive portfolio.

Sedans and Sportbacks: A3, A4, A5 Sportback, A6, A7, A8; S3, S4, S5 Sportback, S6, S7; RS 3, RS5 Sportback, RS 7.

SUVs and wagons: A4 Allroad, Q5, SQ5, Q7, Q8, e-tron.

Coupes and Convertibles: A3 Cabriolet, A5 Coupe, S5 Coupe, RS 5 Coupe, A5 Cabriolet, S5 Cabriolet, TT Coupe, TTS Coupe, TT RS Coupe, TT Roadster, R8, R8 Spyder.

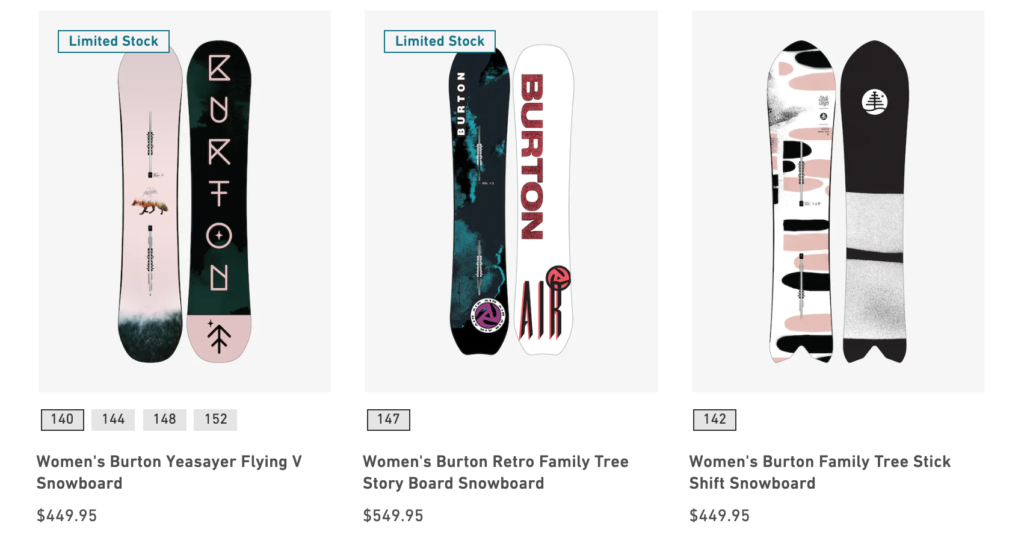

Here’s how Burton Snowboards maps out:

A mixed bag of mostly evocative names.

Some examples (their portfolio is enormous so this is not exhaustive).

Men’s (sample): Family Tree Mystery Fish, Family Tree Stun Gun, Process Flying V, Custom X Flying V.

Women’s (sample): Feelgood Flying V, Yeasayer Flying V, Family Tree Resonator Powsurf, Family Tree Backseat Driver.

The second exercise we run when we’re considering an architecture is to compare two brands in the same space and how their architectures lay out relative to one another. The main questions we’re looking to answer is “are we able to understand which product is right for us?” and “can we tell which is more or less premium?”

Let’s look at Huawei and Apple.

Huawei:

HUAWEI P30 Pro

HUAWEI P30

HUAWEI Mate X

HUAWEI Mate 20

HUAWEI Mate 20 Pro

HUAWEI Mate 20 X

PORSCHE DESIGN HUAWEI Mate 20 RS

HUAWEI P20

HUAWEI P20 Pro

HUAWEI nova 3

HUAWEI Mate 20 lite

PORSCHE DESIGN HUAWEI Mate RS

HUAWEI Mate 10

HUAWEI Mate 10 Pro

PORSCHE DESIGN HUAWEI Mate 10

HUAWEI P smart+ 2019

HUAWEI P smart 2019

HUAWEI Y9 Prime 2019

HUAWEI Y7 2019

HUAWEI Y9 2019

HUAWEI Y6 2019

HUAWEI Y5 2019

HUAWEI Y7 Prime 2018

HUAWEI Y7 2018

HUAWEI Y6 Prime 2018

HUAWEI Y6 2018

HUAWEI Y9 2018

HUAWEI Y5 Prime 2018

HUAWEI Y5 Prime 2018

A huge portfolio with a deeply confusing naming system. If I were managing the naming of this portfolio I’d suggest creating clear tiers for premium, mass market, and entry level devices using short and poetic names. Then I’d assign a clear numeric system that signifies how premium a device is within each tier as well as developing a more interesting method for including generation in the name using symbols. Then you’d find your tier by name, dial in how premium of a device you’d like using the number system, and find the latest model according that year or seasons symbol.

Apple:

iPhone XS

iPhone XS Max

iPhone XR

iPhone X

iPhone 8 Plus

iPhone 8

iPhone 7 Plus

iPhone 7

iPhone 6s Plus

iPhone 6s

iPhone 6 Plus

iPhone 6

iPhone SE

Apple has used a clear system from iPhone 6 through iPhone 8 — though they’re now at an inflection point with their tenth generation rolling over to whatever they’re going to do for their eleventh. Going to 11 feels bad because it feels less premium and even worse is suddenly switching to roman numerals before they make whatever leap they’re going to make after ten. They also made a switch from Plus to Max, though it’s still fairly clear what’s going on there. In both instances the architectures they are applying are decent. If I were managing the naming of this portfolio I’d suggest dropping the “i” from iPhone — to be more in line with Apple Watch — and developing a more interesting generation system, same as what I’d recommend for Huawei: get poetic, use symbols, or follow the classic fashion generation with F/W 19 and S/S 19. Again, nobody wants to buy and iPhone XVIIR or an iPhone 29 Max.

In the automotive space VW and Audi have been intertwined for decades, both owned by the Volkswagen group. Their brands and their model naming, however, couldn’t be more different — despite the fact they share some of the same underlying technology, platforms, and parts.

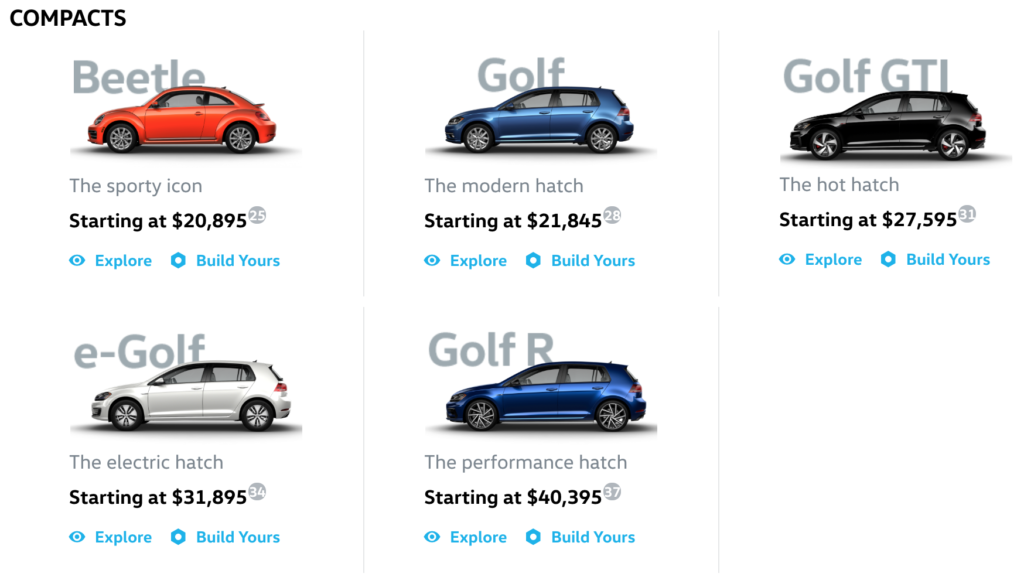

VW

Sedans

Jetta

Jetta GLI

Passat

Arteon

SUVs

Tiguan

Atlas

Wagons

Golf SportWagen

Golf Alltrack

Compacts

Beetle

Golf

Golf GTI

e-Golf

Golf R

Convertibles

Beetle Convertible

The naming is a bit haphazard and a touch playful. It takes some time and context to understand the lineup. If I were managing the naming of this portfolio I’d stick to real words for names: Tiguan and Arteon aren’t great because they mean just about nothing. Atlas is, as a name, great and appropriate for such a massive vehicle.

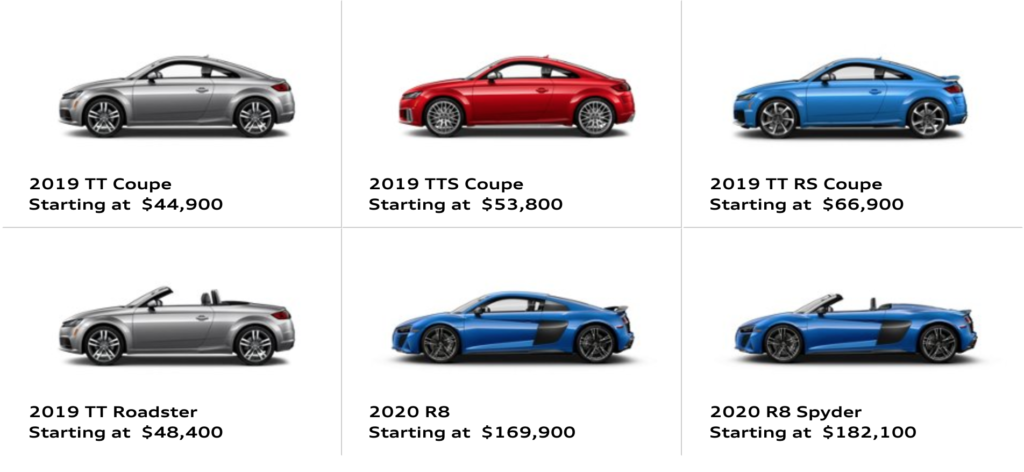

Audi

Sedans and Sportbacks

A3

A4

A5 Sportback

A6

A7

A8

S3

S4

S5 Sportback

S6

S7

RS 3

RS5 Sportback

RS 7

SUVs and wagons

A4 Allroad

Q5

SQ5

Q7

Q8

e-tron

Coupes and Convertibles

A3 Cabriolet

A5 Coupe

S5 Coupe

RS 5 Coupe

A5 Cabriolet

S5 Cabriolet

TT Coupe

TTS Coupe

TT RS Coupe

TT Roadster

R8

R8 Spyder

This system is logical and clear, albeit a little boring. Audi hasn’t changed much in decades. More or less, the smaller the car the smaller the number, with the exception of the TT line and the R8 line. Most standard models start with an A or a Q and jump to or add S, the R and S as you get racier and sportier. If I were managing the naming of this portfolio I’d rename the e-Tron because it’s way out of left field and then keep everything the same.

At A Hundred Monkeys we’ve learned how easy it is to get lost in the weeds when building or modifying a naming architecture — how easy it is to keep tacking on words and spinning off sub-brands and adding modifiers — however, we use these two testing structures to keep the focus where it needs to be: on grabbing attention and helping people figure out what’s right for them.