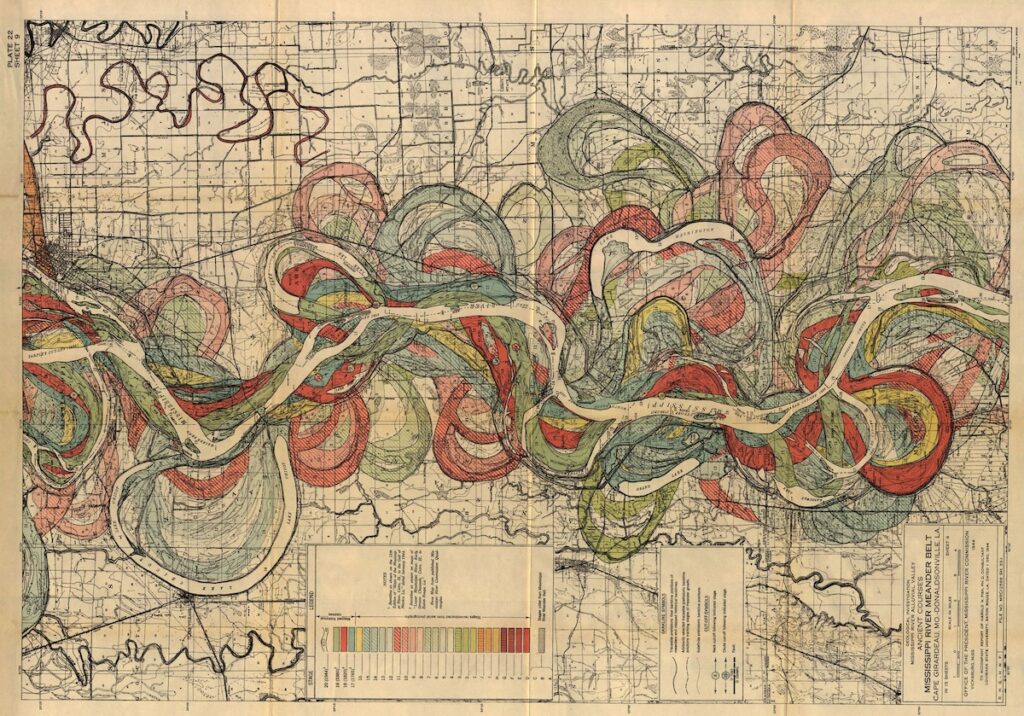

Brand equity: a river in reverse

June 11, 2024

Reading Time: 5 minutes

Filed under Branding, Naming, Naming Architecture

Understanding the flow of brand equity within an ecosystem

We have a saying at A Hundred Monkeys that “brand equity flows upstream.” It’s something we remind ourselves whenever we work on naming ecosystem projects. Essentially it means that any sub-brand or branded element (feature, service, tool, etc.) that doesn’t get a name sends the brand equity of that element upstream to the product or company responsible for the experience. Now, that might sound a bit abstract, so let’s look at some examples.

Brand equity flows upstream

In-N-Out:

In-N-Out has a tiny menu by industry standards and everything on it is named descriptively. So while McDonalds has the Big Mac and Burger King has the Whopper, In-N-Out has the hamburger—no branded sauces, recipes, or meal deals. Sure, we could call the Double Double a bit of a branded product, but it’s very descriptive. They do, however, have a not so secret menu with things like “Protein style” and “Animal style”. This does a great job of keeping everything simple at first glance while creating depth and mystery for people to sink their teeth into.

Apple Retina display:

By naming their display technology, Apple is telling us that it’s a standout feature worth paying attention to. For a minute, let’s imagine a world where they kept developing their display technology in the exact same way, but didn’t name it at all. We would just attribute these advancements to Apple and their products. Instead of “check out Apple’s new Super Retina XDR display” you would just say “the display on my new iPad is brilliant,” or “Apple continues to make great displays.” Since the release of the first Retina display in 2010, Apple has used Liquid Retina, Super Retina, Super Retina XDR, Retina 4.5k, Retina 5k, and Retina HD—diluting the equity of “Retina” and making it harder for their customers to keep up.

Square:

Square has around thirty products in five categories. They clearly took the decision to name products descriptively: Square payments, Square POS, Square banking—the list goes on. So while all of these products have names, none of them are brands. The only brand is Square, which is both easy to understand for their audiences, and easy to manage for them. Restraint has its benefits, especially for brands with big product portfolios.

Neutrogena Helioplex:

Neutrogena has branded the UVA/UVB protection in their sunscreens as Helioplex Technology. This decision is interesting because most sunscreens don’t brand their sun protective abilities. Compared with Techron below, there isn’t an obvious additive or difference—”broad spectrum” protection from UVA and UVB rays is industry standard. So essentially Helioplex sits between Neutrogena and their customers. Contrast this with the sunscreens by Vacation which have a bunch of exotic product names like Orange Gelée and Chardonnay Oil but zero branded elements, just descriptively calling out “Broad-Spectrum protection” and “SPF-30.”

Chevron with Techron:

Techron is a fuel additive released in 1981 and included in all Chevron gasoline products starting in 1995. I think it’s safe to say that most consumers can’t tell different brands of gasoline apart. They might like one brand over another but the underlying product is very much a commodity. Techron created a branding layer where there hadn’t been one by introducing a fuel additive at the pump. So while Shell and Exxon and Arco had gas, Chevron had Techron.

Oakley lenses:

Oakley introduced Prizm lens technology in 2015 to increase contrast and color for sporting applications. Now this technology has made its way into most of their lenses—84% at time of writing. So if Oakley was known for their lenses before Prizm, what does Prizm do? Are Oakley glasses without Prizm lenses inferior as a result of Prizm’s proliferation through the Oakley catalog?

Five key principles of brand equity within ecosystems:

- Focus on what’s different and protect-able. Adding branded elements creates something else for people to remember and something else for the company to market. This doesn’t mean it’s always a bad idea, but if you can’t think of a clear reason why a feature or ingredient needs its own brand, proceed with caution.

- As brand ecosystems grow, the role of wayfinding becomes more important. If you have a lot of products or technologies or features, it becomes harder for people to intuit the differences between them. This is why giving everything you create its own name is usually a trap. We say this as professional namers who would take just about any opportunity to give something a cool name.

- Avoid branding industry standard features or technology. If it’s something everyone is offering like anti-lock brakes or polarized lenses, people generally want to check the box, not remember that you have a special name for something everyone else has.

- Be consistent. A lot of ecosystem branding happens on an ad-hoc basis. There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with this, it’s just how business happens—companies are more likely to release products and features slowly than all at once. Every sub-brand you create is a flag you put in the ground. It tells your audience what’s worth paying attention to. Brands with zero sub-brands can be just as compelling as brands that name everything. Consistency also applies to modifying sub-brands over time. When brands iterate on products using “Plus” then “Max” then “Ultra,” it just creates dilution and confusion. If you can make a better version, great. Improve the sub-brand you already have.

- Look at what’s persistent and pervasive. Having sub-brands at the fringes of a portfolio tends to have low recognition and create headaches for brand and marketing teams. When sub-brands show up across a portfolio, it indicates that it’s something a brand values and believes in.